William Gilbert (/ˈɡɪlbərt/; 24 May 1544 – 30 November 1603), also known as Gilberd, was an English physician, physicist and natural philosopher. He passionately rejected both the prevailing Aristotelian philosophy and the Scholastic method of university teaching. He is remembered today largely for his book De Magnete (1600), and is credited as one of the originators of the term “electricity”. He is regarded by some as the father of electrical engineering or electricity and magnetism.

While today he is generally referred to as William Gilbert, he also went under the name of William Gilberd. The latter was used in both his and his father’s epitaphs, in the records of the town of Colchester, in the Biographical Memoir that appears in De Magnete, and in the name of The Gilberd School in Colchester.

Gilbert argued that electricity and magnetism were not the same thing. For evidence, he (incorrectly) pointed out that, while electrical attraction disappeared with heat, magnetic attraction did not (although it is proven that magnetism does in fact become damaged and weakened with heat). Hans Christian Ørsted and James Clerk Maxwell showed that both effects were aspects of a single force: electromagnetism. Maxwell surmised this in his A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism after much analysis.

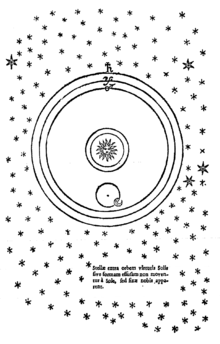

Gilbert’s magnetism was the invisible force that many other natural philosophers, such as Kepler, seized upon, incorrectly, as governing the motions that they observed. While not attributing magnetism to attraction among the stars, Gilbert pointed out the motion of the skies was due to earth’s rotation, and not the rotation of the spheres, 20 years before Galileo (but 57 years after Copernicus who stated it openly in his work “De revolutionibus orbium coelestium” published in 1543 ) (see external reference below). Gilbert made the first attempt to map the surface markings on the Moon in the 1590s. His chart, made without the use of a telescope, showed outlines of dark and light patches on the moon’s face. Contrary to most of his contemporaries, Gilbert believed that the light spots on the Moon were water, and the dark spots land.

Besides Gilbert’s De Magnete, there appeared at Amsterdam in 1651 a quarto volume of 316 pages entitled De Mundo Nostro Sublunari Philosophia Nova (New Philosophy about our Sublunary World), edited—some say by his brother William Gilbert Junior, and others say, by the eminent English scholar and critic John Gruter—from two manuscripts found in the library of Sir William Boswell. According to Dr. John Davy, “this work of Gilbert’s, which is so little known, is a very remarkable one both in style and matter; and there is a vigor and energy of expression belonging to it very suitable to its originality. Possessed of a more minute and practical knowledge of natural philosophy than Bacon, his opposition to the philosophy of the schools was more searching and particular, and at the same time probably little less efficient.” In the opinion of Prof. John Robison, De Mundo consists of an attempt to establish a new system of natural philosophy upon the ruins of the Aristotelian doctrine.

The First Engineer In The World

No comments:

Post a Comment